On reflection it was inevitable that I would join the army. All my early childhood was spent either playing Cowboys and Indians in the woods, or soldiers amongst the bombed buildings. I was born with a wanderlust and would wander off at every opportunity, oblivious to my parents’ concern. My mother would allow me to the front gate which was secured, but no further.

But inevitably I would climb the obstacle and go exploring the neighbourhood, I was meant to be outdoors. My parents would give the kids in the street money to search for me. The kids loved this as it boosted their pocket money and I think they encouraged me to go mooching.

When choosing between either indoors or outdoors it was no contest, as the council house we lived in was far from luxurious. We now complain about double glazing, but our house was lucky to have single glazing and if a window got broken it was a long time before it was replaced. Usually a piece of cardboard was used which helped keep the flies in during summer and the cold in during the winter. You could open the front door and the cold would rush out.

Laying under a poncho in a tropical rain forest with the rain lashing down often reminded me of my childhood and the old rain coat.

As a kid I loved the rain and would take an old Mackintosh (rain coat), and lay under it in the back garden.

The trouble was the coat was not waterproof but I would still lay under it for hours. When older I would go to the woods, which were a good three miles away in the centre of a golf course.

There was a pond in the middle of the wood where we would fish. We would have one eye on the float and the other looking out for Peg Leg. He was the golf course greenkeeper who had an artificial leg, and although disabled he had a fair turn of speed, so we had to be alert. We used to camouflage our clothing with grass and leaves and blacken our faces like commandos. I realise now that it was part of my basic training.

It was always a pleasure to go camping, which I did at every opportunity. In the school holidays, a group of us would head for the country. We would be armed with catapults, axes and fishing rods, but little else. We would clean a pillbox out on the banks of the Medway and live in it for weeks. These disused emplacements were often used as toilets but after much scraping and sweeping, it would become habitable. The foul smell was quickly replaced by smoke after a fire was lit in a corner. We would huddle around the blaze, oblivious to the smoke. We burned coal, which we collected from the railway line close to our camp site, the coal fell off the tender when the trains negotiated a sharp bend. Our diet consisted of whatever was in season in the fields around the area. We would sneak out at night and dig potatoes and raid the orchards. I preferred this to my home in London. We had freedom and could stay up as late as we liked.

It was good preparation for sneaking through the woods trying to avoid contact, which I found myself doing in Borneo years later.

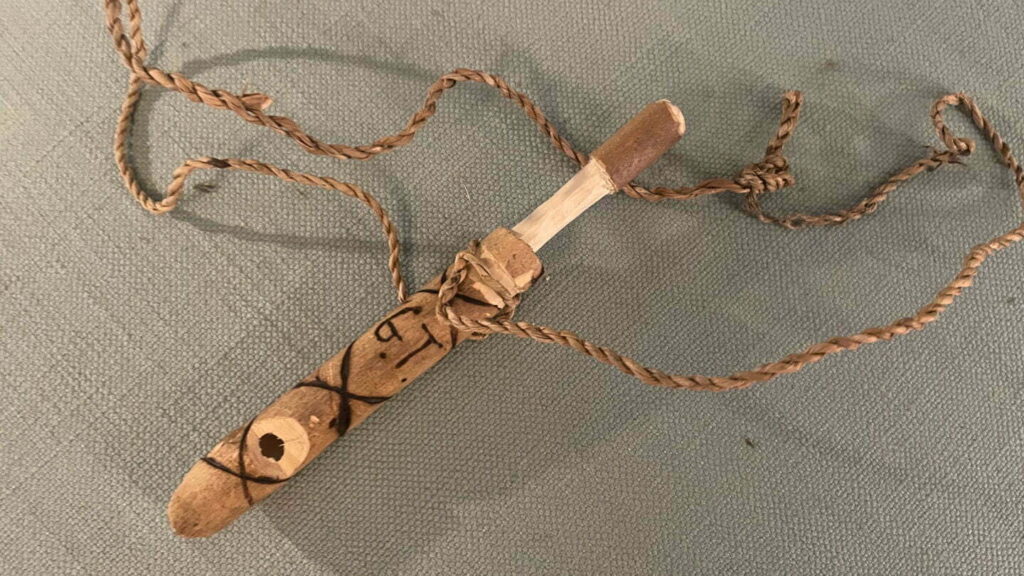

When I started work we still went camping at every opportunity, but now we had money in our pocket. This was spent in the army surplus shop where we bought our camping kit. I bought a leather sheepskin-lined jacket that I rarely removed, a pair of dispatch riders boots that came up mid-calf and weighed a ton, a submariner’s woollen jersey and a pilot’s survival dinghy. This was a small inflatable one man affair with canvas paddles that fitted over the hands. This was the envy of the gang and I spent hours floating up and down the Medway in this marvel of rubber. My pride and joy nearly spoiled my survival record. I was dressed in the sheepskin, jersey and heavy boots, with an axe in my belt, a catapult round my neck and two pockets of stones. I launched the dinghy as usual, nimbly leaping in avoiding getting wet. I placed my hands into the paddles and started paddling. One minute I was a cockle shell hero, next a deep sea diver. Somehow I capsized the dinghy and sank like a stone. The jersey alone absorbed a few thousand gallons of Medway and with all the other paraphernalia I found myself standing up on the river bed. I couldn’t get my hands out of the paddles to jettison anything and I stood there rooted to the spot, a hazard to shipping. They say your life flashes past your eyes in such circumstances and after the initial panic a calmness descends. I started thinking of the tin of beans I had left in camp and started walking.

I walked till my head broke the surface and saw all my mates lining the bank. They couldn’t believe it and reckoned I had stayed under water for ages. All I wanted was to dry out and eat that tin of beans.

My mate had a good idea and dipped his finger in petrol and lit it. He quickly blew out the flame and said if I soaked my wet clothes in it and let it burn for a short while my clothes would dry quickly. At the time this sounded like a good idea, so I stripped off and wrung out the excess. My mate poured a generous amount of fuel on the pile and set it alight. Well to cut a long story short, I went home wrapped in a blanket and my mate was no longer my mate.

I learned many things from this experience the main one being you cannot swim if overdressed without a floatation aid. The second one is you cannot dry out your clothing instantly. Always respect water no matter how innocent it looks, it’s what’s hidden under the surface that’s dangerous. Broken bottles, weeds and old bikes can all cause injuries. Cold water can seriously upset even the strongest of swimmers. Never dive into water until you have tested the depth and never swim near any pipes or weirs. This time of year rivers and lakes can freeze, so stay off the ice. If boating, canoeing, or rafting, wear a flotation aid.

After one long camping expedition we used the toilets in Tonbridge to clean up before getting the train home. We were caked in mud and smelled of wood smoke. I left the toilet and looked down the high street and couldn’t believe my eyes. I rubbed them and looked again, before going back inside. I didn’t mention what I had seen in case I was hallucinating – I thought many days of being smoked in a poorly ventilated pillbox had taken their toll. My mate went outside and I was relieved to hear him shout, “you won’t believe this but there’s an elephant walking down the high street.” The circus was in town and they were parading to advertise this fact.

All the camping and fishing I did as a kid taught me so much. I learned to recognise all the birds, trees and plants. I thoroughly recommend it to all parents to get their children interested in nature. They will never be bored as it is changing daily. Switch off the computers and get outside. Practicing the country code will give them a sense of responsibility and help preserve our beautiful country.

We have a motto, ‘always leave the place better than you found it’. This was certainly the case with the pillboxes. I must admit that I preferred living in that emplacement than I did in my house in South East London. The freedom, adventure and experiences could never be learned in a classroom. How many teenagers have seen the sun rise and set and looked at a starry sky. We tend to divide our day up with regular meals and a set bed time. All that goes out the window when outdoors. Eat when you are hungry and sleep when you are tired, you can pack so much more into 24 hours than normal. If nothing else it will help you appreciate things that we take for granted like running water, flushing toilets and electric lights.

I always look forward to the first snows that fall on the Brecon Beacons. There’s nothing more relaxing than taking a tent, a good book and the means of making a curry, and camping out for a few days. It’s the ideal scenario if you are trying to write a book. Inspiration is gained and all distractions eliminated. I would recommend this to anyone. It helps us refocus our lives and get away from all the hustle and bustles and get another aspect on any troubles.

So head for the hills it’s a great way of getting over the abuses of comfort eating and inactivity that we often put our bodies through each winter.